|

Fryderyk Chopin wrote dreamy nocturnes and lush, romantic harmonies

that hang at the edge of dissonance until you can’t stand it any more,

then resolve with a sigh.

Except when he didn’t.

Listen to this spare moonscape of a

piece, played by an an anonymous YouTube contributor whose visual

presentation and hesitations in the right hand highlight the awkwardness

of the timing and harmonies. I’ve always thought this piece could

have been written by Bartok.

He was an improviser who hated having to notate his

ad-libbed keyboard inventions. He was at his worst as a performer, and

at his best late at night among inebriated friends, when he could use

the piano to mimic the quirks of humanity and create off-the-cuff

miniatures of consummate sweetness. [Georges]Sand gave him the domestic

security to do this. Chopin’s art is essentially an intimate one: he

wrote no symphonies, operas or quartets, and the accounts of his

piano-playing quoted by Zamoyski all stress the light, nuanced touch of

his playing – worlds apart from the keyboard-versus-orchestra battles so

beloved of the romantic era.

— from a

book review by Andrew Clark of Adam Zamoyski

Happy birthday, Fred — 200 years old today.

|

1 March 2010

|

|

Two measures of happiness

Memory plays tricks. There’s a big difference between being

happy in your life and being happy about your life.

If we assess how happy we are from moment to moment we get one

result, and if we recollect and summarize, we get a different result.

Overlap between the two is about 50%.

It’s the remembered happiness that feeds into our thinking about the

future and our decision-making. ‘We think of our future as

anticipated memories.’

—

TED talk by Dan Kahneman, 2010

|

2 March 2010

|

|

Ancient writing

There are two claims this week that enrich our picture of what life

was life for our ancestors tens of thousands of years in the past. One

is graphics on egg shells from 60,000 years ago: were they mere

decorations or labels or, perhaps, name ids of the people who owned

them?

—

New Scientist article by Kate Ravilius

April Nowell and Geneviève van Petzinger have collected graphics from

the walls of caves on 5 continents, and and they make the remarkable

claim that some of the same symbols are used in the same way by

cave-dwellers all over the world, as long ago as 30 thousand years ago.

If this is so, were they communicating across vast distances? Or

is there some genetic basis for symbolic language, so that it comes out

in similar symbols? Or was (even earlier) writing conserved over

tens of thousands of years of diaspora?

—

more from Kate Ravilius

Here is a site with lots of pictures that claims to see evidence for ancient

ships and visits from space aliens.

|

3 March 2010

|

|

Aurora Leigh

...

Natural things

And spiritual,—who separates those two

In art, in morals, or the social drift

Tears up the bond of nature and brings death,

Paints futile pictures, writes unreal verse,

Leads vulgar days, deals ignorantly with men,

Is wrong, in short, at all points. We divide

This apple of life, and cut it through the pips,—

The perfect round which fitted Venus’ hand

Has perished as utterly as if we ate

Both halves...

Who paints a tree, a leaf, a common stone

With just his hand, and finds it suddenly

A-piece with and conterminous to his soul

Why else

do these things move him, leaf, or stone?...

| No lily-muffled hum of a summer-bee, |

|

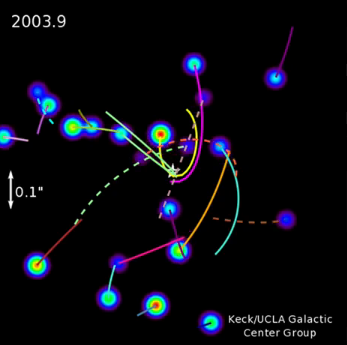

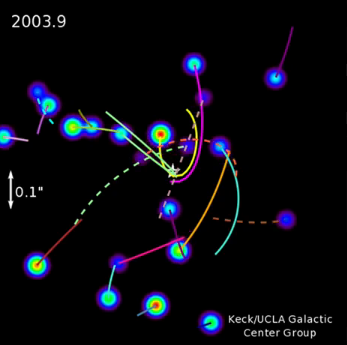

How do we know there’s a black hole at the center of our

galaxy?

We can’t see the black hole, but we can see stars that are close to

it either orbiting around it or looping in and out like a comet.

These stars are so close to the black hole that their orbits are very

rapid and the curves very tight.

Watch the movie!

Notice the scale - 0.1" on the left. This refers to one tenth

of one second of arc, the angle subtended in the sky. At the

distance to the galactic center, this corresponds to about 1/8 of one

light year. The fastest stars are moving that far in a year’s

time, indicating that they are traveling about 1/8 the speed of light.

From the simple Newtonian form of the gravity equation, it is possible

to calculate how big a mass is necessary to deflect the path of

something traveling that fast, at that radius.

What we know is that there is a huge mass, equivalent to millions of

stars, in a very small volume. We rely on Einsten’s theory to tell

us that whenever so much mass is crammed into such a small space, it

must collapse into a black hole.

|

5 March 2010

|

|

“I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I

set him free.”

—

Michelangelo, born this day in 1475

“Lord, grant that I may always desire more

than I can accomplish.”

|

6 March 2010

|

|

IS there any cause which you espouse, any activity you pursue, any

good that you admire that you consider so sacred as to be above

laughter?

This is your opportunity to seek an outside perspective.

Another name for the Great Mystery is the Great Absurdity.

— Josh Mitteldorf

|

7 March 2010

|

|

Quiet

THERE is a flame within me that has stood

Unmoved, untroubled through a mist of years,

Knowing nor love nor laughter, hope nor fears,

Nor foolish throb of ill, nor wine of good.

I feel no shadow of the winds that brood,

I hear no whisper of a tide that veers,

I weave no thought of passion, nor of tears,

Unfettered I of time, of habitude.

I know no birth, I know no death that chills;

I fear no fate nor fashion, cause nor creed,

I shall outdream the slumber of the hills,

I am the bud, the flower, I the seed:

For I do know that in whate’er I see

I am the part and it the soul of me.

— John Spencer

Muirhead

|

8 March 2010

|

|

‘A maverick romantic lyricist in a turbulent age’

If you don’t know Samuel Barber’s

Adagio for

Strings, then by all means introduce yourself. But he left us

a great deal more enchanting, hypnotic music. The

Cello Sonata is

a new favorite of mine: just when you are trying to decide whether the

theme is meditative

or just brooding, a surprise pops out of nowhere. The

Canzone of the Piano Concerto has been recast as a popular flute solo, but I

think the original is even better.

Samuel Barber would have been 100 years old today.

|

9 March 2010

|

|

A dream within a dream

(after Edgar Allan Poe)

|

Accept this promise from my heart

Your soul from mine shall never part

Exploring, venturing from the chart –

Seeking, chasing Atman’s beam

Knowing all is but a dream;

Beyond imagination’s scope

A future humbling faith and hope

Relinquish visions, open wide

To possibilities untried.

All that we may know or seem

Is but a dream within a dream.

|

I stand astride the ocean’s roar

Caress its wide, luxuriant shore

And I hold within my hand

A single grain of golden sand –

Ephemeral symbol of the small

Fairy dust, a crystal ball

And microcosm of the All.

In awe! as I release my grasp

And find my hands in prayerful clasp

In awe! And full surrender, brave

I join the overarching wave,

Thinking: all we know or seem

Is but a dream within a dream. |

— JJM*

*Searching for mystical verse this morning, I reread

Poe’s masterpiece

and tried to imagine what he might have written had he

not had so much to drink the night before.

“It is by no means an irrational

fancy that, in a future existence,

we shall look upon what we think our present existence, as a dream.”

|

10 March 2010

|

|

It takes only a handful of individuals to really make a difference...

In a study published in Proc Natl Acad, researchers from the

UCSD and Harvard provide the first

laboratory evidence that cooperative behavior is contagious and that it

spreads from person to person to person. When people benefit from

kindness they ‘pay it forward’ by helping others who were not originally

involved, and this creates a cascade of cooperation that influences

dozens more in a social network.

—

Press release in Science Daily

Research article by James Fowler and Nicholas Christakis

I don’t have much faith in these lab experiments in psychology -

people behave differently from in the real world, and the sample

population of people who partricipate in psych studies is not

representative. Nevertheless, in this case I think they’ve got it

right.

—

JJM

|

11 March 2010

|

|

Urban farms?

Costs:

- Land is vastly more expensive—Despommier

recommends highrises.

- Energy must be spent for lighting in lieu of the sun

- Rainwater is forgone so all must be supplied as irrigation

Savings

- No pests or weeds means no pesticides or herbicides

- Perishables need not be air-freighted or trucked to market, but

can be sold locally

- No waste of water or fertilizer

- No weather hazards

- With 24-hour lighting and climate control, many crops can be

grown each year

The claim is that the savings outweigh the costs. ‘Vertical

farming ’ may be more fuel-efficient, with less environmental

impact than standard factory farming practices. Plants can be

grown hydroponically, or with very little soil. Minerals, nitrates

and phosphates are injected instead of being dumped on the ground as

fertilizer. Waste is minimized.

‘The biggest issue is where to get the energy. As much as

possible will come from solar and wind. More comes from

incinerating the parts of plants we don’t eat...the rest comes from

recycling the energy from liquid municipal waste.’

—

Scientific American article by Dickson Despommier

supplementary

article by Mark Fischetti

brief summary and online dialog

|

12 March 2010

|

|

On the resilience of joy

In November of 1755, Lisbon was devastated by an

earthquake that left

the city in ruins, with more than 10,000 dead.

700 Km away in Paris, Voltaire found his philosophical tenets shaken.

How can anyone believe in an all-powerful, beneficent God?

Voltaire wrote a poem explicating his newfound pessimism. In a

preface, he wrote

The author of the poem on The Disaster of Lisbon is

not an adversary of the illustrious [Alexander] Pope, whom he has always

admired and loved: he thinks like him on practically all matters; but,

pierced to the heart by the misfortunes of mankind, he wishes to attack

the abuse that can be made of that ancient axiom ‘All is for the best’.

He adopts in its place that sad and more ancient truth, recognized by

all men, that ‘There is evil upon the earth’; he declares that the

phrase ‘All is for the best’, taken in a strict sense and without hope

of an afterlife, is merely an insult to the miseries of our existence.

Voltaire’s poem occasioned a controversy between him

and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who, in a long ‘Reply to M. de Voltaire’,

explained pessimism such as Voltaire’s as being the product of the

unnatural and unhealthy life of the pampered and privileged

intellectual. Ask a humble craftsman or a Swiss peasant whether evil

predominated over good in human life, as Voltaire suggests, and you

would get a very different answer.

— Read

article and full text of the poem in English and

in French

Ce monde, ce théâtre et d’orgueil et d’erreur

Est plein d’infortunés qui parlent de bonheur.

In this theater of hubris, amid gaunt

devastation

Live many a poor soul who speaks of elation.

— Voltaire

|

13 March 2010

|

|

For Einsten’s birthday

Because Einstein has earned our reverence, we are willing to ponder even

his simplest pronouncements, and assume that our meditations will be

rewarded. We invest what he says with depth. This is always a boon,

whether Einstein turns out to be right or wrong, because any deep and

sustained application of our brains is likely to produce satisfying

results.

Einstein once said that the most important question we can ask is, “Is

the Universe friendly?” He was speaking, presumably, of basic physical

laws which, against all odds, has made possible life and consciousness

and brains that can reflect upon the universe which gave them birth. It

was not until twenty years after Einstein’s death that specific evidence

was compiled for the “friendliness” of physical law, and the

Anthropic

Principle was formulated. The basic idea is this: There are a handful of

fundamental constants that physics takes as a starting point, things

like the speed of light and the strength of gravitational attraction.

These numbers appear to be completely arbitrary, even in the deepest

theories of physics that we have. And yet, we notice that the Universe

would be vastly different if these constants were even slightly

different from the values they actually have. In all cases, it appears

that the Universe with altered fundamentals would be far less

interesting, far less rich in possibilities: no stars, no chemical

elements, no possibilities for complexity.

Some people might see in this situation the handiwork of a beneficent

God. This would not be a God who intervenes from day to day in human

affairs, but a God who set the Universe in motion with a rich set of

possibilities built in. Perhaps the idea is compatible with the Deistic

religions born of the Enlightenment in the 17th and 18th centuries. In my

favorite variation of the idea, God is a universal consciousness, and

consciousness creates the physical Universe (and animates it with life)

as a playground for its entertainment and a university for its

edification.

Another idea – hardly less radical – that has captured the imaginations

of astronomical theorists is that there is a multiplicity of universes,

not in physical communication with each other. The different universes

are characterized by different fundamental constants in all possible

combinations. Only a tiny percentage of these universes support the

possibility of complex phenomena, including life and consciousness, and

it is no accident that we live in one such universe, because the others

have no beings capable of observing them. Physicists are fond of saying

that our Universe may not be typical in the set of all universes, but it

is typical among the subset of universes that contain physicists.

— Josh Mitteldorf

|

14 March 2010

|

|

Is the Universe Friendly? (Continuation of themes from the last two days)

Is the world governed by a beneficent hand assuring that all will turn

out for the best? Or is nature cruel and violent, riddled with random

and meaningless disasters that will bring us down in the end?

Most people, when they pose this philosophical query are really asking,

“Is it possible for one in circumstances such as mine to be happy?”

Ironically, the answer they are looking for is “no”. How much more

comfortable it is to feel that we are heroic for having eked out, by our

own virtue and force of character, whatever measure of happiness we have

known, rather than to imagine that we have failed to benefit from the

munificence that fate has bequeathed to us.

Due to twin breakthroughs in science and pure thought, I am at last able to

offer you a definitive answer to the question of Optimism vs Pessimism,

or the Problem of Evil,

as first formulated by Epicurus in the third century B.C:

It is as you suspected. It has not been possible for you to be any happier,

any more serene or more content with your life than you have been

up until this moment. Indeed, you have done absolutely the best that was

possible, heroically, and beyond all expectations.

But – equally remarkable – circumstances have fundamentally changed.

Starting today, it is newly possible for you to experience a freedom, a

joy, and a serenity you have never known in the past. What is more, this

transformation may not require any fundamental alteration of your

outward circumstances, although it is likely that the change in your

inward state will produce ripples that gradually bear fruit in the world

around you, enhancing cooperation, diffusing conflict, and ultimately

supporting a better and more deeply satisfying life experience for

all those within your sphere of influence, yourself included.

Also revealed is that the wisdom necessary to effect this

transformation is already present within you, and that you know what to

do to discern it.

— JJM

|

15 March 2010

|

|

Turning a data explosion into a knowledge explosion

Imagine a new

Library of Alexandria. Imagine an archive that contains

all the natural and social sciences of the West—our source-critical,

referenced, peer-reviewed data—as well as the cultural and literary

heritage of the world’s civilizations, and many of the world’s most

significant archives and specialist collections. Imagine that this

library is electronic and in the public domain: sustainable, stable,

linked, and searchable through universal semantic catalogue standards.

Imagine that it has open source-ware, allowing legacy digital resources

and new digital knowledge to be integrated in real time. Imagine that

its Second Web capabilities allowed universal researches of the bibliome.

—

from a

New Republic article by Lisbet Rausing

The way that information is managed touches all areas of life. At the

turn of the 20th century new flows of information through channels such

as the telegraph and telephone supported mass production. Today the

availability of abundant data enables companies to cater to small niche

markets anywhere in the world. Economic production used to be based in

the factory, where managers pored over every machine and process to make

it more efficient. Now statisticians mine the information output of the

business for new ideas.

—

from an

Economist article by Kenneth Cukier

|

16 March 2010

|

|

The Inner History of a Day

No one knew the name of this day;

Born quietly from deepest night,

It hid its face in light,

Demanded nothing for itself,

Opened out to offer each of us

A field of brightness that traveled ahead,

Providing in time, ground to hold our footsteps

And the light of thought to show the way.

The mind of the day draws no attention;

It dwells within the silence with elegance

To create a space for all our words,

Drawing us to listen inward and outward.

We seldom notice how each day is a holy place

Where the eucharist of the ordinary happens,

Transforming our broken fragments

Into an eternal continuity that keeps us.

Somewhere in us a dignity presides

That is more gracious than the smallness

That fuels us with fear and force,

A dignity that trusts the form a day takes.

So at the end of this day, we give thanks

For being betrothed to the unknown

And for the secret work

Through which the mind of the day

And wisdom of the soul become one.

~ John O’Donohue

|

17 March 2010

|

|

“The power structure and its liberal apologists dismiss the rebel as

impractical and see the rebel’s outsider stance as counterproductive.

They condemn the rebel for expressing anger at injustice. The elites and

their apologists call for calm and patience. They use the hypocritical

language of spirituality, compromise, generosity and compassion to argue

that the only alternative is to accept and work with the systems of

power. The rebel, however, is beholden to a moral commitment that makes

it impossible to stand with the power elite. The rebel refuses to be

bought off with foundation grants, invitations to the White House,

television appearances, book contracts, academic appointments or empty

rhetoric. The rebel is not concerned with self-promotion or public

opinion. The rebel knows that, as Augustine wrote, hope has two

beautiful daughters, anger and courage--anger at the way things are and

the courage to see that they do not remain the way they are. The rebel

is aware that virtue is not rewarded. The act of rebellion defines

itself.”

—Chris

Hedges

|

18 March 2010

Anti-war protestors,

DC 1967

|

|

A woman who put hope and Gaia in the same sentence

Elinor Ostrom won the 2009 Nobel Prize for her stories and theories

of spontaneous human cooperation, un-coerced by central authority.

When people own a resource in common, there is a temptation for

individuals to grab their share and more, pre-empting the next person’s

selfishness. This is the ‘tragedy of the commons’. Ostrom

shows us that human nature is pliable and can lead to cooperative

outcomes just as easily as selfishness; that it is the enforced greed of

capitalism that is the problem, not human biology.

‘We need to get people away from the notion that you

have to have a fancy car and a huge house. Some of the homes that have

been built in the last 10 years just appall me. Why do humans need huge

homes? I was born poor and I didn’t know you bought clothes at anything

but the Goodwill until I went to college. Some of our mentality about

what it means to have a good life is, I think, not going to help us in

the next 50 years. We have to think through how to choose a meaningful

life where we’re helping one another in ways that really help the Earth.’

—

Elinor Ostrom in YES magazine

|

19 March 2010

|

|

Paracelsus

TRUTH is within ourselves; it takes no rise

From outward things, whate’er you may believe.

There is an inmost centre in us all,

Where truth abides in fullness; and around,

Wall upon wall, the gross flesh hems it in,

This perfect, clear perception—which is truth.

A baffling and perverting carnal mesh

Binds it, and makes all error: and, to KNOW,

Rather consists in opening out a way

Whence the imprisoned splendour may escape,

Than in effecting entry for a light

Supposed to be without.

— Robert Browning (more of the poem

here)

|

20 March 2010

|

|

Bach had a day job

Bach struggled during his early life to find steady employment.

When, at the age of 38, he applied for a job as choir director in Leipzig,

he considered his prospects remote. Georg Philipp Telemann was

clearly the leading applicant, but he had better opportunities. The

second choice was Christoph Graupner, and when he turned down the offer,

the parish was ‘compelled to fall back on mediocrities’. Bach was

grateful for the stipend, and stayed in this post the rest of his life.

His duties:

He was required to teach music and other subjects, especially Latin,

to the boarders at the upper school, and to give them individual tuition

whenever he thought it was needed; he was to direct the choir in each of

Leipzig’s four churches on alternate Sundays, often composing the music

himself; he was to supervise the organists and other musicians in each

place; he was to take charge of ordering and inspecting all the musical

scores and parts – and all the instruments as well – for the services in

all four churches . . . and those were only some of his strictly musical

duties. Every fourth week it was his responsibility to get all the

students up at 5-o’clock in the morning, after which, according to the

school regulations,

‘He is to ensure that fifteen minutes later all

are assembled for prayers in the auditorium downstairs. He is to say prayers again at 8 p.m., and to note

that no one is absent and that no lights are taken into the dormitories. While

supervising meals he must see that there is no boozing, that Grace is said in German

before and after every meal, and that the Bible or a history book is read

during the repast. It is his duty to make sure that the scholars return in full

number and at the proper hour from attending funerals and weddings etc.. He must

particularly satisfy himself that none comes home having drunk too much. He shall

hold the key to the infirmary and visit all patients there confined. Absence from

his duty during the day entails a fine of four groschen, and at night of six.’

The thought of Bach being a dormitory inspector and meal supervisor for

twenty-seven years fairly boggles the mind. Hardly more so, though, than his daily

routine and the range of his activities. A sixteen-hour working day was normal, and he plotted

it with all the precision of a military campaign. Academic lectures were scheduled daily

between 7.00 and 10.00 in the morning and from 1.00 to 3.00 in the afternoon. In addition

to these were the daily singing exercises plus individual vocal and instrumental lessons.

And then there were the regular services at the four churches, as well as frequent special

services such as weddings and funerals. For long stretches, Bach would be composing

weekly cantatas, in addition to other music, and in addition to fitting in his such

demanding extra-curricular projects as the Collegium Musicum concerts at the Coffee House, his

ever-more-famous organ recitals, his thriving sub-career as an instrumental teacher to

the aristocracy, the various calls on his services as an assessor of organs and harpsichords,

and so on. Nor should we forget, as he never did, his devotion to his wife and

ever-expanding family,

— Jeremy Siepmann

Johann Sebastian Bach is 325 years old today.

|

21 March 2010

|

|

Bach, continued...

Imagine Bach at the end of his life. He had been a devoted head

of family, who lost his much beloved first wife at a tender age, and

endured, too, deaths of ten of his twenty children. He had a sense

of his legacy, though few of his peers appreciated it, and he had worked

assiduously to prepare the gifts he would leave to future generations.

At 65, he had weak lungs, and was completely blind. An operation

to try to recover his sight had turned out disastrously.

But his disposition remained unfailingly positive to the end.

Bach had a mathematical mind, combined with a deep and literal faith in

the Christian God. He was ready to meet his Creator.

Unable to write, he dictated to his son-in-law his final creation, a

contrapuntal work based on a simple chorale melody,

I step before thy

throne, O God. The transparent serenity of this piece is a

testament to Bach’s unwavering faith. There is no hint of tragedy

or even of drama, not a trace of self-consciousness. Each of the

four chorale phrases is developed to a conclusion which is, like death

itself, both inevitable and completely unexpected.

Listen

to my own performance of Bach’s last composition – JJM

|

22 March 2010

|

|

Commit this to memory – then tear it up

Most moral thinkers – from Socrates to Christ to Francis of Assisi –

eschewed the written word. Once things are written down they become

codified. Passages of sacred or philosophical texts are twisted,

reinterpreted and rewritten to accommodate those in power, bolster the

unassailability of religious institutions, and silence dissidents.

Writing freezes speech. George Steiner calls this the ‘decay into

writing.’ This is especially dangerous for ethical and moral philosophy,

since, where philosophy and prescription see only virtue and vice, in

reality human actions combine the two to different degrees.

—

Chris Hedges (from

I don’t Believe

in Atheists)

“Where rigid, formal obedience to law allows

the adherent to avoid ethical choice, the truly moral life grapples with

the inscrutable call to do what is right, to reach out to those who are

reviled, labeled outcasts or enemies, and to practice compassion and

tolerance, even at the cost of self-annihilation. And all ethical action

begins with an acknowledgment of our sin and moral ambiguity.”

|

23 March 2010

|

|

Stages

As every flower fades and as all youth

Departs, so life at every stage,

So every virtue, so our grasp of truth,

Blooms in its day and may not last forever.

Since life may summon us at every age

Be ready, heart, for parting, new endeavor,

Be ready bravely and without remorse

To find new light that old ties cannot give.

In all beginnings dwells a magic force

For guarding us and helping us to live.

Serenely let us move to distant places

And let no sentiments of home detain us.

The Cosmic Spirit seeks not to restrain us

But lifts us stage by stage to wider spaces.

If we accept a home of our own making,

Familiar habit makes for indolence.

We must prepare for parting and leave-taking

Or else remain the slaves of permanence.

Even the hour of our death may send

Us speeding on to fresh and newer spaces,

And life may summon us to newer races.

So be it, heart: bid farewell without end.

—

Hermann Hesse

|

24 March 2010

|

|

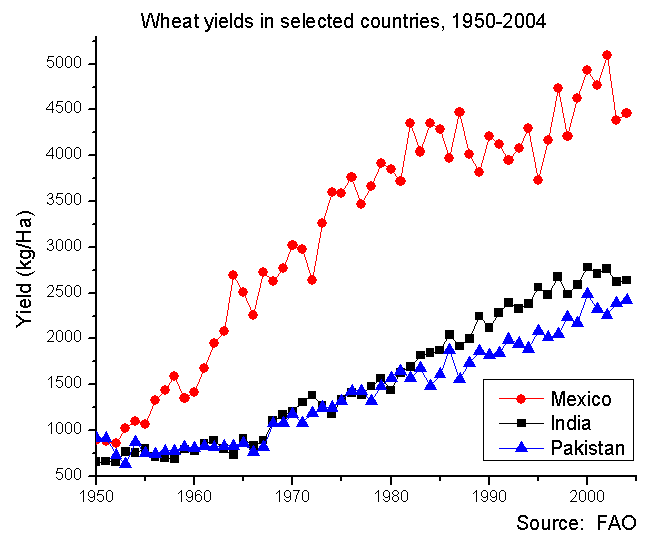

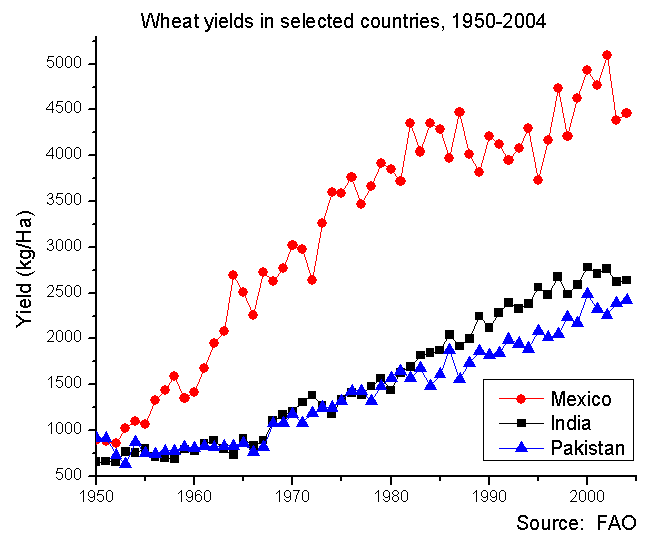

Who was Norman Borlaug?

Before there were GM crops, the old-fashioned way to increase crop

yields was to cross different strains to create varieties that resisted

pests and harsh weather, while yielding larger harvests in shorter

times. In the mid-20th century, Norman Borlaug was the world’s

foremost practitioner of this art.

Borlaug left his roots as an Iowa farm boy to work for Dupont as a

chemist, then left Dupont at the end of World War II to breed wheat in

Mexico. Within a few years, he had developed a fast-maturing

variety that could be grown in two crops each year, which yielded

nevertheless more grain in each crop than the varieties that had been

used before.

(It turns out that the key was to outcross with dwarf varieties.

Over the milennia, natural selection in grasses such as wheat had

favored plants that squandered their energy growing higher so they could

grab more sunlight. This is a zero sum game, however, and in a field

full of short plants, the short plants did just fine.)

In the 1960s, Borlaug went to work on rice.

Biologist Paul R. Ehrlich wrote in his 1968 bestseller The

Population Bomb, ‘The battle to feed all of humanity is over ... In the 1970s and 1980s

hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.’

Ehrlich said, ‘I have yet to meet anyone familiar with the situation who thinks India

will be self-sufficient in food by 1971,’ and ‘India couldn’t possibly feed two hundred million more people by 1980.’

Borlaug bought the time that the developing world needed to bring down fertility rates and tame the population bomb.

Norman Borlaug, born this day in 1914,

won the

Nobel Peace Prize in 1970, lived to see the maturity of the Green

Revolution, and died last September at the age of 95.

|

25 March 2010

Crop yields have tripled in South Asia, quintupled in Mexico

|

|

Kary Mullis has a proposal for a successor to antibiotics

Antibiotics were the medical revolution of the 20th Century, slashing

death rates from infectious disease. But there are two limitations

to antibiotics: (1) they don’t work for viruses, and (2) bacteria evolve

resistant strains over a period of decades, then share their resistance

with other bacteria through horizontal gene transfer.

In

this interview at Edge.org, Mullis starts from the beginning,

explains to us how the immune system works, and how a very artificial

trick can be used to bend a universal biological process and gain an

advantage over microbes.

His idea uses the best-developed strength of modern biochemistry: our

ability to determine the sequence of DNA fragments, and to synthesize

new DNA strands with any desired sequence.

All our bodies already have learned early in life to recognize and

respond to some common invaders. Our immune systems recognize

characteristic chemical fragments that they wear on their cell

membranes. But when a new invader comes along, it can take weeks

for our bodies to learn to recognize it, then grow enough specific

antibodies to that invader to mount an effective response.

The trick which Mullis is developing is this: We can create a

DNA sequence that has the new invader’s signature at one end and the

old, recognized signature at the other end. This is a molecule

that will bind tightly to the new invader, and tag it so that our immune

systems are tricked into thinking that they are an old, familiar

invader. Our immune systems then have a leg up on the invader, and

can arrest its growth at an earlier stage.

Here is

another description of the system that Mullis calls altermune

from Mullis’s web page. If I understand it correctly, the system

uses aptamers, which are RNA fragments that bind uniquely not

to other RNA or DNA, but to a protein sequence found on the cell’s

surface.

|

26 March 2010

|

|

It began in mystery and it will end in mystery,

but what a savage and beautiful country lies in between.

– Diane Ackerman

|

27 March 2010

|

|

Humility and Humiliation

You might infer from the etymology that humiliation is the process by

which a person socialized into a stance of humility. But our psyches are less straightforward

and logical than this. In reality, it seldom happens that people acquire

genuine humility through an experience of humiliation. Humiliation may

lead to despair and depression, or to denial, or to a chain of oppressive

relationships in which each victim becomes perpetrator in the next link.

None of these outcomes is conducive to the virtue of humility.

Why is this?

Humility is about belonging and trust in the competence and goodwill

of others. It is a sense of community, an appreciation

of interdependence, and a warm feeling of being cared for by peers,

without whom we could not thrive. In this sense, humiliation is the

opposite of humility: it is an exclusion through shaming, an expulsion

from community.

We adopt a stance of humility when we feel most secure. We

teach humility when our actions are trustworthy and caring.

— Josh Mitteldorf

|

28 March 2010

|

|

A green annuity

It took decades before solar power became cost effective for

mainstream applications. It could be more decades before consumers

get the message, and a further wait until they have liquid savings that

could be invested in solar retrofits.

A San Francisco company, SolarCity

is diving into the gap, making solar panels available with no upfront

cost, and structuring the leases so that the end user sees savings from

the first month.

Scientific American ‘World-changing

ideas’

NYTimes article

CBS news

Note: Solar nominally still needs government

subsidies and tax incentives to be cost-effective, but that’s only

because oil and nuclear are so heavily subsidized, and coal burners

are not required to pay the full cycle cost, including environmental

costs and global warming.

|

29 March 2010

|

|

Silence of the Stars

When

Laurens van der Post one night in the

Kalahari Desert

told the Bushmen he couldn’t hear the stars singing, they didn’t believe

him. They looked at him, half-smiling. They examined his face to see

whether he was joking or deceiving them. Then two of those small men

(who plant nothing, who have almost nothing to hunt, who live on almost

nothing, and with no one but themselves) led him away from the crackling

thorn-scrub fire and stood with him under the night sky and listened.

One of them whispered, ‘Do you not hear them now?’ And van der Post

listened, not wanting to disbelieve, but had to answer, ‘No.’ They

walked him slowly, like a sick man, to the small dim circle of firelight

and told him they were terribly sorry; and he felt even sorrier for

himself and blamed his ancestors for their strange loss of hearing,

which was his loss now.

— David Wagoner

(Traveling

Light)

|

30 March 2010

|

|

Growth of the spirit - it takes a village

Many of us sense that something is trying to emerge between us that’s

more important than anything we can experience in our solitary practice.

There’s something in the collective dimension that transcends what is

possible in individual spirituality.

— Craig Hamilton

“The next buddha will be a sangha*.”

—

Thich Nhat Hahn

*A sangha is a Buddhist meditation community. Perhaps Thich’s

message is that the time when we could be inspired by individual,

charismatic spiritual leaders is at an end, and that our next step is to

learn closer forms of cooperation and deeper relationships of

trust, in which the self dissolves into a larger entity. Perhaps

religion is following the historic path of polity, moving from

monarchy to democracy.

|

31 March 2010

|

| |